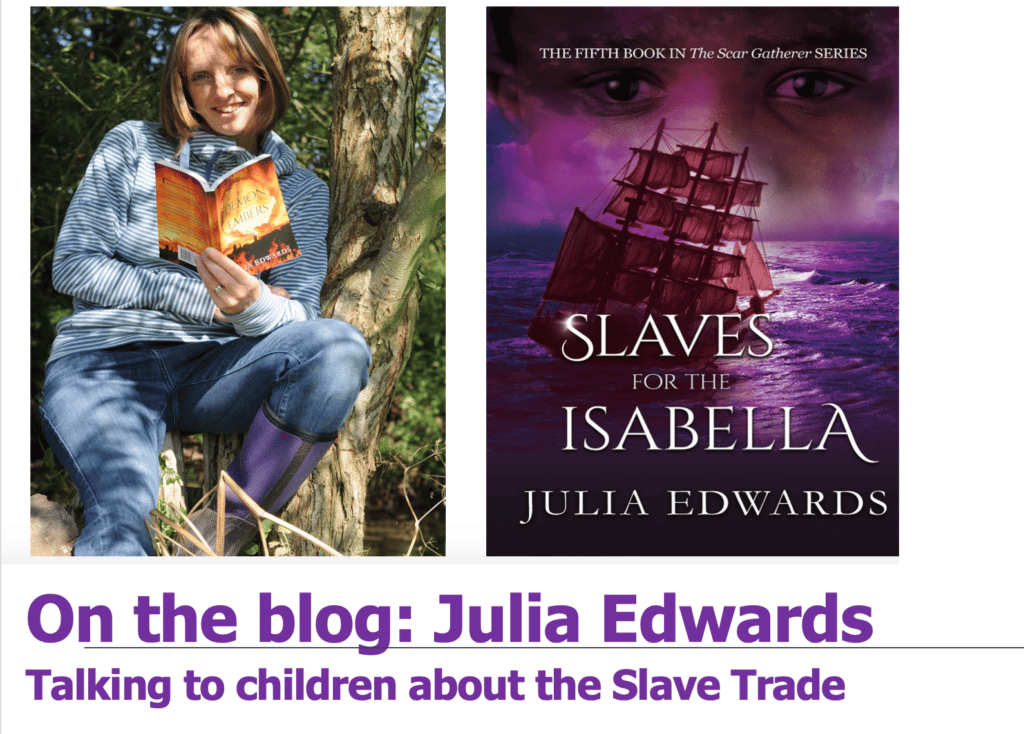

We are delighted to welcome author Julia Edwards to the blog today.

Julia’s series The Scar Gatherer takes readers to different periods of British history, covering popular curriculum topics like the Romans in Britain and the Great Fire of London. But one book in the series, Slaves for the Isabella, covers a particularly dark time in our history – taking readers back to the Georgian period when the Slade Trade was in full swing. Julia stopped by our blog to share her experiences of guiding children into learning about one of the darkest parts of our past…

Author blog

Julia Edwards, author of Slaves for the Isabella (available here)

Taking children into one of the darkest parts of our past

When I started out writing The Scar Gatherer series, I was really excited about the idea of exploring what life was like in the past, living through different periods in history in my imagination so that I could bring them alive for children in my books and in the classroom.

The parts of history I would write about mostly leapt out at me: start with Roman Britain, move on to the Viking Age, definitely include Tudor England even though it’s not on the curriculum at the moment, then survive the Great Fire of London. I knew, too, that I wanted to write about Victorian times and finish up with WW2.

But in between the Great Fire and the Victorians? Well, that was the Georgian era, a long and rather amorphous period without the glamour of Elizabethan England or the technological explosion of Queen Victoria’s reign. The one big thing that was happening throughout Georgian times was the Slave Trade. The moment I realised this, I knew I had a moral obligation to write about it.

Before I took even my very first steps into research for ‘Slaves for the Isabella‘, I felt differently about this book from the others in the series. This book was not going to be fun to write. It should not be fun. Yet it had to be gripping to read. Here was a subject that really mattered! I knew it was the most important book I had written so far, and suspected it might be the most important book I would ever write. (With four more books under my belt since ‘Slaves for the Isabella’, there is no sign yet that I was wrong about this.)

At the same time, I knew I had to engage children if I wanted them to read the book. The story had to be hopeful without falsifying history or detracting from the suffering of millions. It had to be personal – the suffering of millions doesn’t touch us like the suffering of one or two. And it had to take place in England, since the rest of the series was set here.

This meant I had to acquire a detailed knowledge of the horrors of the Middle Passage, the bitterness of arrival in the West Indies, and the appalling nature of life on the plantations. Armed with all this unpalatable information, I had to bring as much of it as I could into a story set in the UK, in a way that was truthful but tolerable for children to read.

It was a daunting challenge!

Since writing ‘Slaves for the Isabella‘, I have visited over 70 schools around the UK as well as abroad and have spoken to several thousand children about the book. During this time, I have seen that children are not only fascinated by the horrors of the Slave Trade, but deeply engaged by the monumental injustice of it. I have discovered, too, that many teachers would really like to teach the subject, but are afraid to do so, aware of their own lack of in-depth knowledge and fearful of saying the wrong thing.

I thought a few tips might be helpful, then, for any teacher hoping to cover this topic. Mine would be as follows:

A general explanation of the Slave Trade should include the following information:

ships from Europe sailed to the west coast of Africa with goods to exchange for innocent people;

these people were transported across the Atlantic to the Americas where they were forced to work as slaves on plantations;

the sugar and tobacco produced on the plantations was then shipped back to Britain;

over time, about 12 million people were taken from Africa like this, yet none of them set foot in Britain except when accompanying their masters back from the plantations to England, with the result that for many years the British public was mostly oblivious to the suffering involved in producing their goods.

When discussing the acquisition by the British of the people we refer to as ‘slaves’, make sure the children understand that these were ordinary, innocent men, women and children, often kidnapped. Using the word ‘slaves’ implies these people were destined for slavery, so try to use the expression ‘enslaved people’ or ‘enslaved Africans’ when referring to them. It is also important to emphasise the morally (though not legally) criminal actions of the British Slave Traders.

Download the diagram widely available online of the Brookes Slave Ship to help the children to understand the realities of the Middle Passage. Besides overcrowding and darkness, they need to know about the inadequate food and water (especially if storms caused the journey to last longer than expected), the insanitary conditions, and the penalties for rebellion.

A good way of explaining the plight of Africans enslaved in this way is to divide the class by percentage to illustrate survival rates:

an estimated 10% didn’t survive the Middle Passage for reasons given above;

a further 30% died in the first three years of enslavement from malnutrition, exhaustion and tropical diseases;

the remaining 60% effectively had a life-sentence to slavery, where any children they had would automatically be born slaves. I often say that the 60% people were the losers. Nonetheless, make sure the children understand the astonishing strength and capacity to survive shown by these people, some of whom were brave enough to risk their lives by rebelling. Enslaved Blacks were just as much part of the campaign to end slavery as famous white men such as William Wilberforce.

When you talk about Abolition (particularly the Abolition of Slavery in 1834, not just the Abolition of the Trade only in 1807), make sure the children know that it was brought about by the British Government paying compensation, not to those who had been enslaved, but to the slave owners for their loss of ‘property’. For example, one slave trader, Thomas Daniel, received a payment of £75,000, equivalent to about £60 million today. This money still benefits the UK, having been invested in railways, insurance companies, the Church of England, some British universities, and the foundation of institutions such as the Natural History Museum.

A detailed lesson plan on the Slave Trade, incorporating all of these tips, can be found in the July 2021 issue of the Teach Primary magazine.

I hope very much that more children will learn about the Slave Trade as a result of ‘Slaves for the Isabella’. Current events such as #BlackLivesMatter and the national conversation about race in the creative industries, media, and business make me hopeful that we may be at a point of societal change, where racial discrimination is addressed like never before.

I do believe, however, that in order to understand and participate in this new society, children need to understand one of the darkest parts in British history and its legacy.

As the infinitely wise Terry Pratchett wrote, “If you do not know where you come from, then you don’t know where you are, and if you don’t know where you are, then you don’t know where you’re going.”

‘Slaves for the Isabella’ is my contribution to knowing where we are, so that we know where we’re going, and so that we can go to a better place!

—————————–

> Order Slaves for the Isabella from BookShop.Org

> Order Slaves for the Isabella from Amazon

> Visit Julia Edwards’ website

Many thanks to Julia for visiting our blog and sharing her guest post with us.

Where next? > Visit our Reading for Pleasure Hub

> Browse our Topic Booklists

> View our printable year group booklists.

> See our Books of the Month.